Auster and My Illusions

It feels right to start with Paul Auster. I owe him my most intense reading experience.

I was 17 and it was a day or two after the New Year. I had moved up to my freezing university pigpen a few days before my housemates returned from the Christmas break. The kitchen was unusually clear of enormous pouches of protein and bowls of defrosting chicken. In my room there was a pile of books under the snow covered skylight I needed to read for my course but instead of tackling them I decided to read an unknown author to me. Kept warm by condensated breath with only my own company The New York Trilogy kept me captive for two days.

I chased that feeling thereafter. Every January since then I have read an Auster book, instead of a resolution it's more of a New Year habit. It’s a strange way to force myself to start the year with ardour. I decided to progress chronologically considering I initially started at the beginning.

This year I completed The Book of Illusions.

The hero, David Zimmer, is a professor who recently lost his wife and children in a plane crash. He struggles to find enjoyment until he coincidentally discovers one of Hector Mann’s short comedies, a presumed deceased actor and director of the 1920s. One scene from the film was the only thing that had Zimmer ‘actually laughing out loud’ since the death of his family. He sees this as a vital indication. Zimmer decides to travel cross-country to view the entirety of Mann’s filmography and write a book on the director. The subsequent completion causes Mann’s wife to write Zimmer a letter ordering him to meet Mann in New Mexico where it is divulged that Mann has been relentlessly creating films in a home-made studio.

The narrative continually blurs the lines between reality and illusion, drawing parallels between the two men’s lives and Mann’s films. Auster suggests illusions can cause reality to be subjective.

As a filmmaker this struck me as oddly inspirational as reality is often predictable and commonly feels like entrapment, at least for me. If somebody can craft illusions from bedroom to studio it gives the hope that life shouldn’t be taken at face value and that one has autonomy over their own narrative path. I guess this idea has been done heavy handedly in The Truman Show and Stranger than Fiction but more expertly in Adaptation. It’s the idea that what you put on the page can somehow affect your own life. A writer’s fantasy.

Typically, Auster’s characters share a sense of displacement while grappling with their identity and a sense of purpose. Many of them are solitary, only experiencing brief intense relationships before returning to isolation, which is probably why I like him so much. It’s another strange fantasy of mine - I could never escape the romantic image of the lost artist. The characters often struggle to find stability in a deafening world. Mann is no exception. By castrating the characters from normalcy Auster heightens that previous idea of illusion and reality. If one is alone, one tends to daydream.

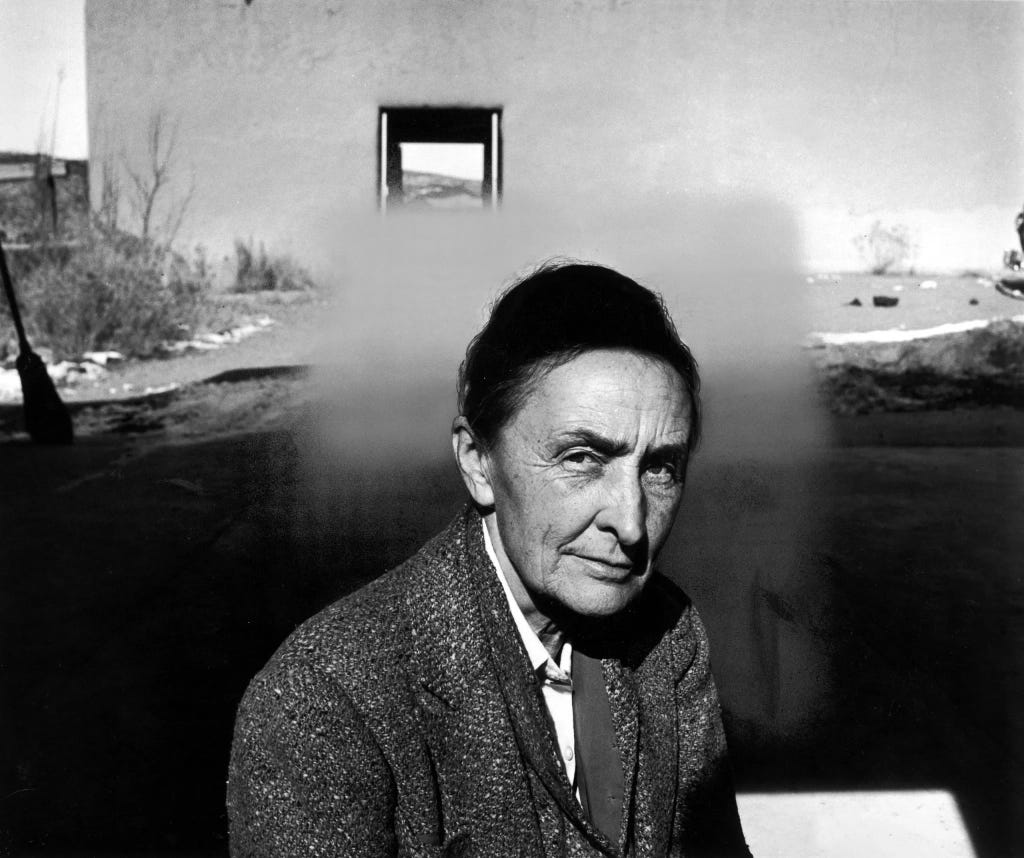

The director fled to New Mexico after facing a transformative event. He is a melting pot of numerous artists that moved to the same landscape at the dawn of the twentieth century. The dry blinding landscape beckoned Georgia O’Keefe, Agnes Martin, Ansel Adams, Max Ernst and William Penhallow Henderson to name a few. New Mexico provided new illusions for all of them.

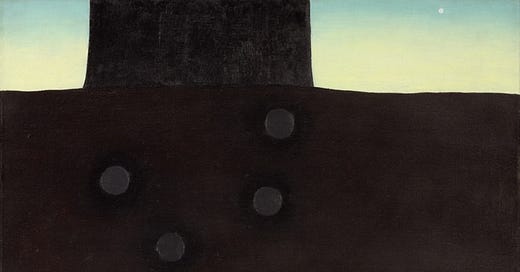

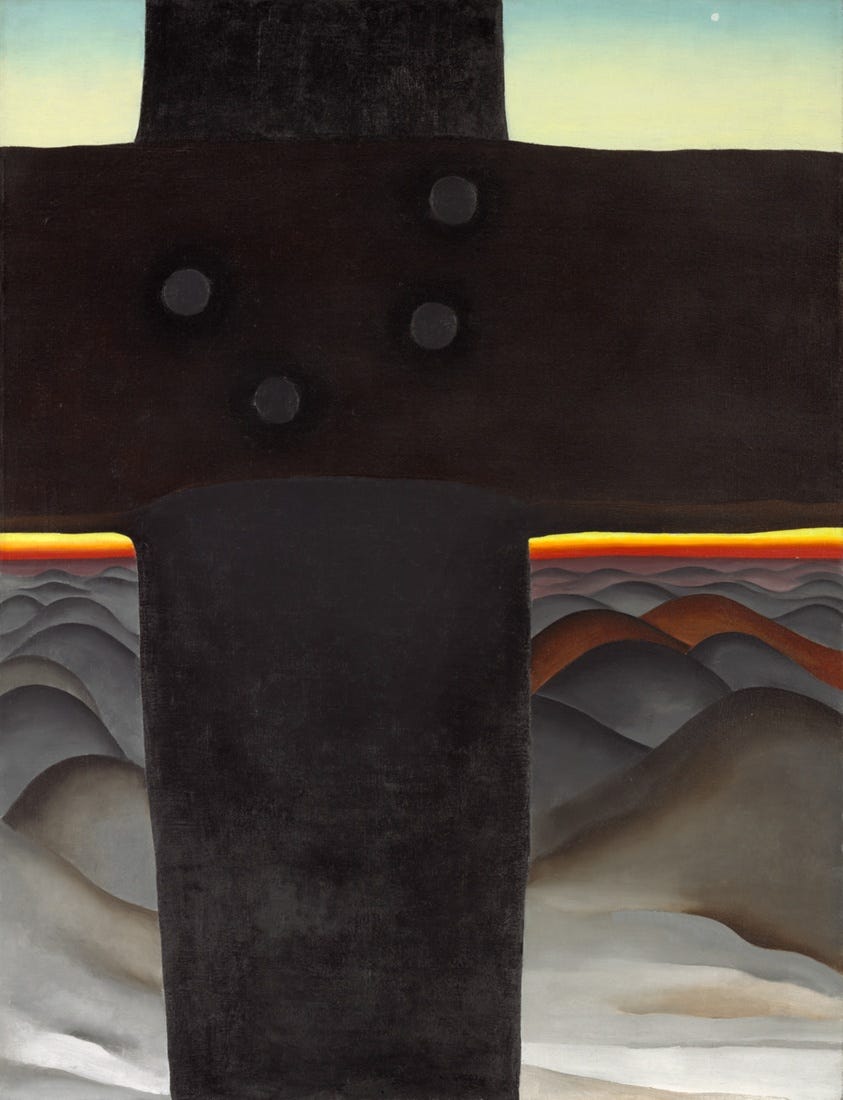

A painting that I find that spiritually channels The Book of Illusion is O’Keefe’s Black Cross, New Mexico. For me, there’s an obvious interest in mortality, loneliness and New Mexico as a kind of purgatory, a place out of time. The black that dominates the image and frames the desert reminds me of Mann’s story as fleeing to New Mexico was a self-made restraint for him. He pinned himself to his own cross.

It’s not promising for my future that I agree restraint is the greatest thing for an artist. These chains can come either from a financial, material or philosophical level. However, restraint commonly ends in frustration and a want for more.

This journal has the potential to be my New Mexico, partly for the fact I don’t like heat and the desert won’t do me any good. It’s the reason why I have named this space ‘Desert Lives’, it’s a chance to live in an illusion. It’s a canvas for me to write, something that I haven’t successfully practised publicly and it’s a space for me to engage with other artists that inspire me in some way. I’m hoping to channel an inner Lou Reed: ‘I’m set free to find a new illusion.’